Abstract forms of living things, natural materials, and geometries found in nature. How Evove embodies biophilic design.

Biophilic design has become a topic of interest for many architects and interior designers. People spend an average of 90% (and more recently +95%) of their day indoors and there is accumulating evidence that bringing elements of nature into our indoor spaces can have enormous benefits, both psychologically, physiologically, and for our cognitive function.

Biophilia is humankind’s innate biological and innate connection with nature. The basic hypothesis of Biophilic design is that the performance and wellbeing of people occupying indoor spaces is greatly improved when they are surrounded by objects and materials that remind them of the outside. This is because humans are inherently attracted to the living and lifelike forms often encountered in natural environments. (13)

Benefits of biophilic design

Research (11) has shown that a strong and routine connection with nature has a restorative effect on mental fatigue. Inversely, Professors of psychology at the University of Michigan who specialised in environmental psychology, noticed that psychological distress was often related to mental fatigue and had a direct relationship to our surrounding environment.

Connection with nature has also been found to reduce tension, anxiety, anger, fatigue and confusion as compared with urban environments devoid of characteristics of nature. And there are physical effects too. Studies have shown that when humans experience the natural environment, they report responses such as the relaxation of muscles, lowering of blood pressure and stress hormone levels. (1)

In a nutshell, the benefits of biophilic design include:

Improved mood (2 3 4)

Reduction in stress (5)

Improved concentration (6)

Improved working memory performance (7 8)

Higher self esteem (3 9)

Increased feelings of energy and vitality (10)

Overall self-perceived feeling of health (11)

So how do we bring nature indoors? We create representations of the living world.

Indirect experiences with nature

Indirect experiences with nature are representations of the living world, without actually having the natural world present. They are non-living recreations of nature such as the objects, materials, colours, shapes, forms and patterns found in nature, which may form an artwork or ornamentation.

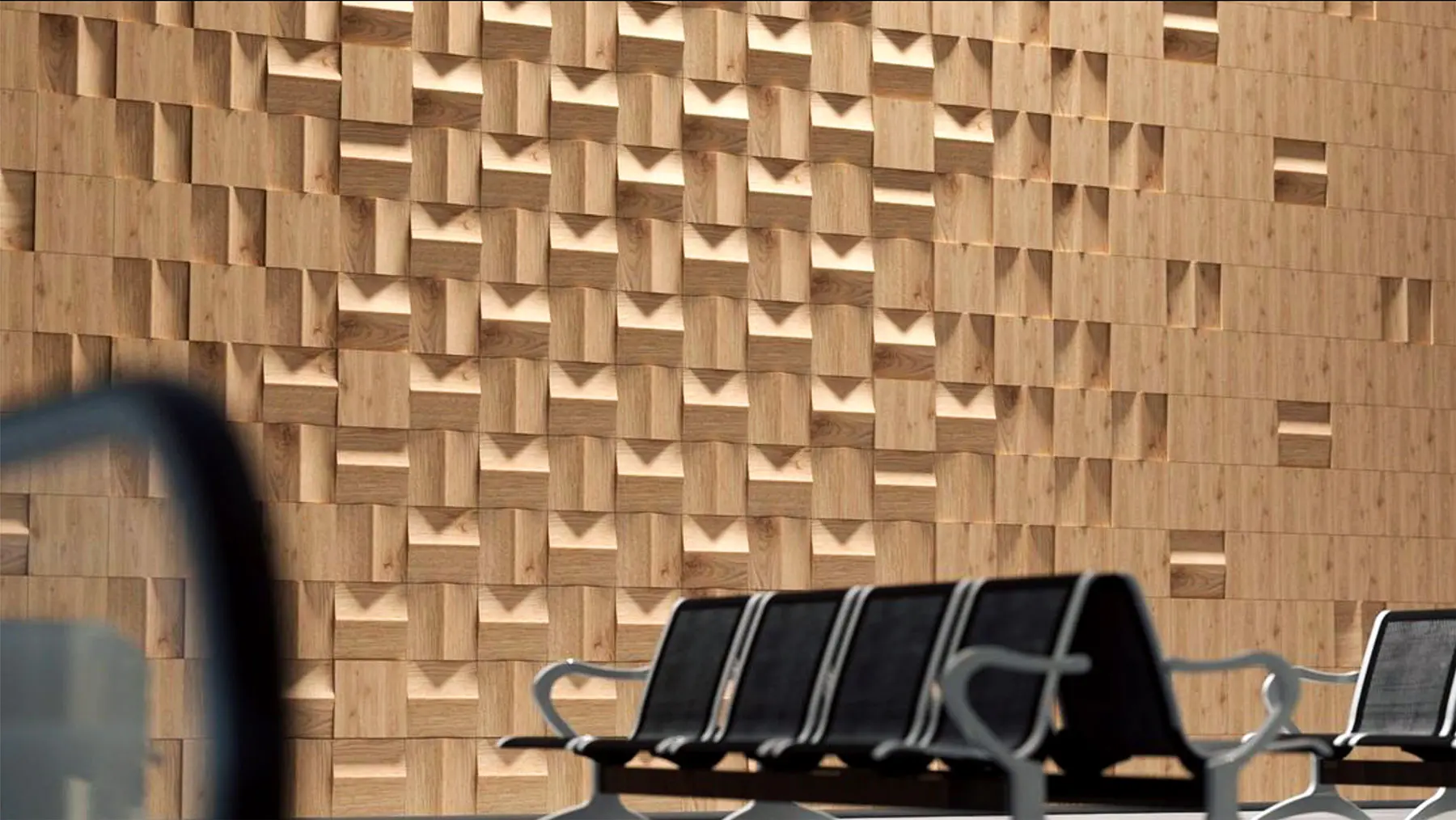

Indirect experiences with nature can be categorised into three biophilic design patterns: abstract forms of living things, natural materials and geometries and hierarchies found in nature.

Abstract forms of living things

Biomorph is a decorative form or object based on or resembling a living organism. It is a symbolic reference to patterned, textured, contoured or numerical arrangements that exist in nature. Examples of this are fluid forms of an architectural facade or curved interior walls.

Natural materials

Natural materials, like timber, can be categorised as an indirect experience with nature. A distinct sense of place can be achieved by using materials and elements from nature that reflect the local ecology or geology. Timber is a great example with its warm and rich grain texture, which is inconsistent visually, helps strengthen the connection between indoors and outdoors.

According to Planet Ark, wood plays a vital role in supporting the principles behind biophilia, as well as having added environmental benefits (50% of its dry weight is carbon). Planet Ark’s report Nature Inspired Design notes that surveyed Australian’s appear to be innately drawn towards wood. Results indicated that wood elicits feelings of warmth, comfort and relaxation and creates a link to nature. According to Planet Ark, multiple physiological, psychological and environmental benefits have been identified for wooden interiors:

Improvements to a person’s emotional state and level of self-expression

Reduced blood pressure, heart rate and stress levels

Improved air quality through humidity moderation

Its use as a long-term store of carbon, helping to fight climate change

Geometries and hierarchies found in nature

This is sometimes referred to as complexity and order. This characteristic or pattern is where rich sensory information adheres to spatial hierarchies like those encountered in nature, such as the mathematical patterns known as fractals. It has been thought that specifically, a space with a moderate amount of fractal usage will keep the space interesting, while not necessarily overwhelming. Symmetry also falls into this category and is perhaps one of the natural tools used by designers, however, it can be used in both reference to natural and artificial design.

While design doesn’t need to explicitly use mathematical sequences, it can often give a space a sense of natural purpose.

References

1 Kellert, S.F., J.H. Heerwagen, & M.L. Mador Eds. (2008). Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science & Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. van den Berg, A.E., Y. Joye, & S. de Vries (2007). Health Benefits of Nature. In: L. Steg, A.E. van den Berg, & J.I.M. de Groot (Eds.), Environmental Psychology: An Introduction (47-56). First Edition. Chichester: WileyBlackwell. pp406.

3 E.O. Wilson, S.R. Kellert – The Biophilia Hypothesis. Island Press, Washington, DC (1995

2 J. Barton, J. Pretty – What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environmental Science and Technology, 44 (2010), p. 3947

3 D.E. Bowler, L.M. Buyung-Ali, T.M. Knight, A.S. Pullin – A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health, 10 (2010), pp. 1-10

4 D. Valtchanov, K.R. Barton, C. Ellard – Restorative effects of virtual nature settings Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13 (2010), pp. 503-512

5 D. Villani, G. Riva – Does interactive media enhance the management of stress? Suggestions from a controlled study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15 (2011), pp. 24-30

6 M.G. Berman, E. Kross, K.M. Krpan, M.K. Askren, A. Burson, P.J. Deldin, …, J. Jonides Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140 (2012), pp. 300-305

7 R. Berto – Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25 (2005), pp. 249-259

8 S. Kaplan – The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15 (1995), pp. 169-182

9 J. Pretty, J. Peacock, M. Sellens, M. Griffin – The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 15 (2005), pp. 319-337

10 R.M. Ryan, N. Weinstein, J. Bernstein, K.W. Brown – Vitalizing effects of being outdoors and in nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30 (2010), pp. 159-168

11 O. Kardan, E. Demiralp, M.C. Hout, M.R. Hunter, H. Karimi, T. Hanayik, …, M.G. Berman Is the preference of natural versus man-made scenes driven by bottom–up processing of the visual features of nature? Frontiers in Psychology, 6 (2015),